A Multimedia Exploration of the Story of Vulcan, Blending Film, Poetry, Sound, Music, Art and Science

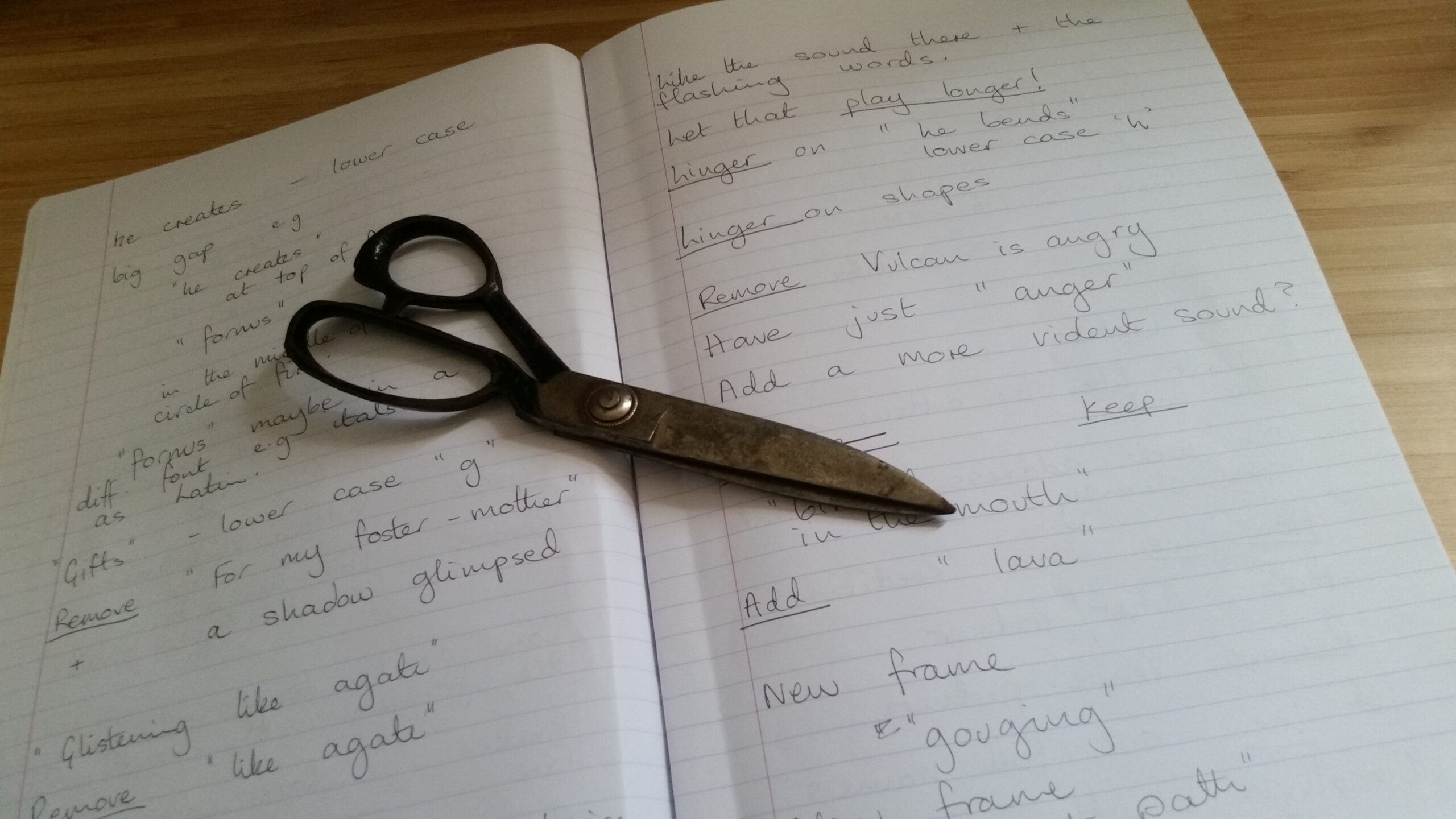

Carolyn’s notebook. Photo Credit. C.Waudby

When Diana Scarborough and I first embarked on The Cradle of Fire film, we discussed what would come first. Pictures? Or words.

Diana was clear she wanted words/poems from me as a frame to hang the film on. So, my starting point was to research the story of Vulcan, then find points of inspiration for the poetry.

Vulcan is one of the lesser-known Roman gods and my knowledge was admittedly thin. He is not a comic book hero, the protagonist of blockbuster films or a popular subject for classical works of art, as our research revealed.

Storyboard

I put a straight narrative account of his story on a Storyboard, a suggestion from our mentor Mike Stubbs. With each frame I suggested possible images Diana could use.

By this time, I’d written a couple of poems so put the titles in the Storyboard at points I thought they may fit. The Storyboard also gave me a coherent timeline to write future poems to.

It was an unconventional way of working. Storyboards are usually filled with images, the text added simultaneously or after.

So this was how Diana and I set out on our film venture. But the final version was quite different. I ended up carrying out four script edits for the final cut.

Once we had something tangible to work with, I travelled down to Cambridge during the summer to spend a couple of days working side by side with Diana at her home.

While she sourced sound and images at her desk, I sat on the patio in her shady garden scrutinising the narrative.

After a couple of hours, we’d have a tea break and share ideas. I would then sit at Diana’s desk with the images she’d found and we’d start to match them with the text.

Female characters

As a result of deeper research and thinking, I realised that the female characters in Vulcan’s life, Juno and Venus, played little part. As creators of the film, and women film makers, we wanted to give them more depth and prominence. So I researched their stories and back stories.

Percy Bysshe Shelley in the Preface to his lyrical drama Prometheus Unbound, Percy Bysshe Shelley: The Major Works, Oxord University Press (2009), states that the Greek tragic writers when selecting a portion of their history or mythology, ’employed in their treatment of it a certain arbitrary discretion’. He goes on to admit that he has employed a ‘similar licence’ with his Prometheus. And so have I with the Vulcan story.

Juno, mother of Vulcan, was not a sympathetic character to modern eyes, throwing her newborn child off a mountain when she realised he was not conventionally handsome.

Initially, parts of the complex Vulcan mythology such as his relationship or lack of it with Juno, had been deliberately left out in our script. But I now wanted to bring that back in, even though it made the film longer.

Another suggestion from our mentor was to incorporate rap into the film. I thought the feelings Vulcan would have towards his mother would make a good subject for this, and wrote a piece in a different style to the poems and script narrative. I’m not a rapper so would not call it rap, but more spoken word/performance. The version in the film uses some improv by the voice actor in keeping with rap tradition.

Women in Cradle of Fire – Film Stills. Credit Diana Scarborough

Vengeance

mother anger

boiling beneath

beggars belief

thrown off a mountain

newborn kid

just because

his face don’t fit

leg was broke

when he hit the sea

fell to the bottom

of the deepest ocean

fell to the bottom

forest of the weird

dark & weed

but raised with love

by a-nother mother

a-nother mother

have to get my own back

hatch a plot

call up my god-power

use my craft

Juno trap

to make her sweat

make her beg

forgiveness

fell to the bottom

of the deepest ocean

fell to the bottom

Carolyn Waudby

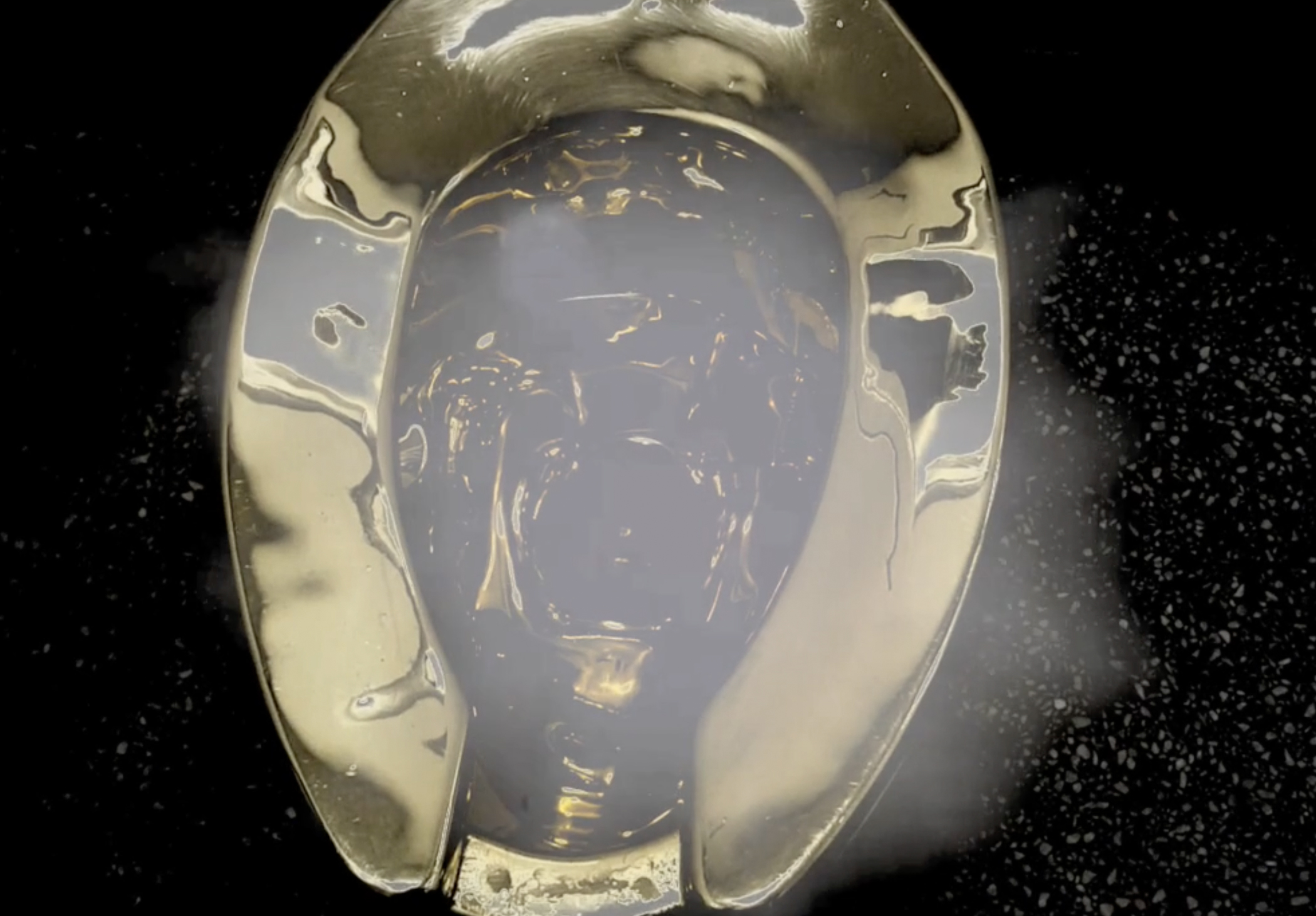

Vulcan’s discovery of his parentage and realisation he was a god led to the plot in which he entraps his mother – literally – with a throne of gold. This is powerful in terms of the story but presented a visual headache. There were no images of gold thrones available for public use and we did not have enough in the budget to pay large licence fees.

Diana came up with the inspired idea of using an image of a toilet made of gold – a visual pun and something contemporary. I loved the injection of humour at this point to an otherwise rather dark saga.

Golden Throne by Maurizio Cattelan features in the film Credit :Eileen Haring Woods/Diana Scarborough

Then there was Venus’ affair with Mars. Again, strong from the point of view of the script but more of a challenge in a film in which there is only voice ‘performance’ from actors.

Venus and Mars Surprised by Vulcan. Hendrik Goltzius, 1585. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

We both agreed the net created by Vulcan to catch the lovers was essential to include (another image problem). I hadn’t written any poems on this section of the story so worked hard on the script to drive the story forwards whilst ensuring it was poetic using techniques of rhyme and rhythm.

he contrives

to weave

a net

for the cheats

iron threads

finer than fuse-wire

and

Vulcan vents

his anger

on his anvil

Venus realises

the threat

she has unleashed

The stanzas were kept short to work with the visuals and not overload the viewer. The layout of the lines was crucial to the look, readability and rhyme/rhythm.

Finally, to add balance, Diana decided she wanted my voice towards the end of the film as it had been at the beginning – so she moved the recording of me reading the poem lava from its original position near the beginning to the final section.

This was one of the first poems of the project I wrote, and, as it references birth, fitted the notion of rebirth – the final word of the film.

In terms of the planet and its future, we wanted to end on a positive note. The images at this point show plants growing in volcanic ash. Life after devastation.

Some of the poems did not make the final cut, such as one on a Volcano Snail, which lives on vents in the deep ocean and has scales like armour. But these will form part of my writing around the wider Cradle of Fire themes.

Post Script:

I’m grateful to poet Chris Jones who, after attending the launch of Cradle of Fire recommended I watch the 1998 film Prometheus by Leeds poet Tony Harrison. Chris remarked that Cradle of Fire reminded him of Harrison’s treatment of mythology, which fuses the story of Prometheus with the closure of coalmines and the decline of the steel industry using footage of real-life events in the north.

The two-hour film is written in rhyme and employs actors. At its core is a mining family of three generations. Within it, one character describes rhyme to another as ‘a pure form of poetry – the language of the gods, not mortals’. Harrison’s working class characters are enobled when they begin to speak in rhyme themselves.

blog by Carolyn Waudby

We’d love to hear from you as we develop the Cradle of Fire project. Please use the contact page to get in touch.

Cradle of Fire is a research and development project, supported by public funds from Arts Council England. We are also grateful for support from our partners and creative collaborators. Read more on the dedicated About pages.

Check our progress to date and future plans via the timeline